Genre fiction by definition must fulfill specific criteria, or why invest in it rather than other differet books, or Batman comics, or movies, or video games? While feeling reenveloped in new Middle Earths is a greatly diminished requisite to today's serious fantasy writers, it was the opposing pole of the genre that made me quit off dragons and dungeons as a kid: the cheap hacks with the surface Tolkien bits soullessly stamped into book after book.

What they've missed, what is misunderstood to anyone that thinks Lord of the Rings fanciful/whimsical and easily recreated, is that it is a war novel, more in common with Band of Brothers than Harry Potter, (despite Rowling's liberal use of every Tolkien bit she could cut and paste). An apocalyptic epic of creative destruction, the shifting of an era through world war; in Rings the heroes know Eden is gone as they defend the remnants of it from becoming Hell. Middle Earth is the last gasp of paradise; even as Tolkien could see the end of his Briton countryside giving way to the world of manufacture.

What they've missed, what is misunderstood to anyone that thinks Lord of the Rings fanciful/whimsical and easily recreated, is that it is a war novel, more in common with Band of Brothers than Harry Potter, (despite Rowling's liberal use of every Tolkien bit she could cut and paste). An apocalyptic epic of creative destruction, the shifting of an era through world war; in Rings the heroes know Eden is gone as they defend the remnants of it from becoming Hell. Middle Earth is the last gasp of paradise; even as Tolkien could see the end of his Briton countryside giving way to the world of manufacture.  There are no churches in Middle Earth. No religion at all. Hobbits are secular and tribal, loving only nature, beauty, peace, tobacco, beer, walks in the forest, and meal time. One can think of a later age of Middle Earth, with Sauron vanquished, and the age of elves and magic forgotten, where trade rights between Minas Tirith and Rohan are deftfully managed by the King, (he who so famously returns); splitting up who gets what percentage of ore out of the mines of Mordor; Horselords quickly revamping the structure of their tribes from nomad to labor what with the primo reconstruction contracts, and building churches to honor the gods they've made, to quote Michael Jagger. Nothing about the end of Lord of the Rings begs for later stories: as the book ends so has magic, so has beauty, so has a connection to the old world. Even as heroes win against the darkness, they lose against time. Infamously missing from the Peter Jackson movies is the Hobbits' return to a Shire under the control of evil wizard Saruman. Whatever you think makes an evil wizard, the last worst spell of this wizard is industrializing the rural hobbit culture. The Shire of Return of the King is as filthy and smog-filled as Bleak House.

There are no churches in Middle Earth. No religion at all. Hobbits are secular and tribal, loving only nature, beauty, peace, tobacco, beer, walks in the forest, and meal time. One can think of a later age of Middle Earth, with Sauron vanquished, and the age of elves and magic forgotten, where trade rights between Minas Tirith and Rohan are deftfully managed by the King, (he who so famously returns); splitting up who gets what percentage of ore out of the mines of Mordor; Horselords quickly revamping the structure of their tribes from nomad to labor what with the primo reconstruction contracts, and building churches to honor the gods they've made, to quote Michael Jagger. Nothing about the end of Lord of the Rings begs for later stories: as the book ends so has magic, so has beauty, so has a connection to the old world. Even as heroes win against the darkness, they lose against time. Infamously missing from the Peter Jackson movies is the Hobbits' return to a Shire under the control of evil wizard Saruman. Whatever you think makes an evil wizard, the last worst spell of this wizard is industrializing the rural hobbit culture. The Shire of Return of the King is as filthy and smog-filled as Bleak House. Unlike the hero fantasies the type nerds get off on, where by living in Conan's skin they can feel all tough and fuckable, Lord of the Rings leaves no character better off than they began; Frodo obviously is never the same; Sam is now a soldier, but what part of returning home, watching his friend's slow demise, and becoming a respectable "mayor", (Shire politics were far more fluid before Saruman's radical takeover), feels like the deserved payback for his heroism and sacrifice? At book's end Aragorn is the king, a far less interesting hero than when he was Strider -- it's sad he'll never be that ranger again. Gandalf the White is not a person, but the end-game strategy of a higher power; never again will the old grey wizard show up at some soon to be new friend's door with magic and the opportunity for adventure. When it's done it's done. And it's done. The point of how Tolkien fans famously re-read Rings; starting over once a year, or every five, or have at it, I believe has to do with how Rings ends in unbearable melacholy; it's a Lear-like void that can leave the reader in a depressive funk, the starting over again is not to read through the increasingly darker and sadder story, but to return to the beginning when the characters and the world have not been touched by war. The first book, Fellowship of the Ring, is consistently considered the weakest of the three as judged on the merits of literature, and equally the most beloved by the fans -- the dichotomy makes sense: as a novel Fellowship is shapeless for the first half; a road journal of flora and fauna as the hobbits rather leisurely find their way into a plot; this is often acknowledged the favorite part of the story for many readers; I know people who reread the first half of Fellowship over and over, and never read anything after about Smeagols, Oliphants, and doomed mountains. Because in this opening, (an opening impossible to faithfully script for the movies for Peter Jackson), is a wistful travelogue over beautiful countryside; a holiday the beloved hobbit characters will never again share.

Unlike the hero fantasies the type nerds get off on, where by living in Conan's skin they can feel all tough and fuckable, Lord of the Rings leaves no character better off than they began; Frodo obviously is never the same; Sam is now a soldier, but what part of returning home, watching his friend's slow demise, and becoming a respectable "mayor", (Shire politics were far more fluid before Saruman's radical takeover), feels like the deserved payback for his heroism and sacrifice? At book's end Aragorn is the king, a far less interesting hero than when he was Strider -- it's sad he'll never be that ranger again. Gandalf the White is not a person, but the end-game strategy of a higher power; never again will the old grey wizard show up at some soon to be new friend's door with magic and the opportunity for adventure. When it's done it's done. And it's done. The point of how Tolkien fans famously re-read Rings; starting over once a year, or every five, or have at it, I believe has to do with how Rings ends in unbearable melacholy; it's a Lear-like void that can leave the reader in a depressive funk, the starting over again is not to read through the increasingly darker and sadder story, but to return to the beginning when the characters and the world have not been touched by war. The first book, Fellowship of the Ring, is consistently considered the weakest of the three as judged on the merits of literature, and equally the most beloved by the fans -- the dichotomy makes sense: as a novel Fellowship is shapeless for the first half; a road journal of flora and fauna as the hobbits rather leisurely find their way into a plot; this is often acknowledged the favorite part of the story for many readers; I know people who reread the first half of Fellowship over and over, and never read anything after about Smeagols, Oliphants, and doomed mountains. Because in this opening, (an opening impossible to faithfully script for the movies for Peter Jackson), is a wistful travelogue over beautiful countryside; a holiday the beloved hobbit characters will never again share.

The depth of this natural world; the history found in the barrow downs, the insistent cataloguing of flowers, roots, and berries on the old roads of the first book builds to the grand set pieces of the later books. While Tolkien's plot is criminally underrated, (See Gollum, the most Shakespeariest figure in literature), the true achievement of Rings is at Helm's Deep, at Mt. Doom, at Isengard; at Bag End, at The Prancing Pony, on Weathertop. Readers don't yearn to see Frodo falter at the end over and over again, but they do yearn to be on Weathertop again, to smell the sausage in the pan, to hear the voices of friends at the fire, to see Strider disappear into the murk on his watch.

This is hard to recreate. Many have tried.

| RR and RR |

A Song of Ice and Fire. I could write a hundred pages on why it's great, (I'm talking about the book series by George RR Martin, not the HBO show Game of Thrones, although I like the show very much), but this is this, (to quote M.Vronsky) : the book series in parts is unabashedly, unashamedly an homage to Tolkien. Martin is confident enough in his own world to not tiptoe around Tolkien; that he's going for Tolkien, in and of the gutsy attempt doesn't make it work; that he understands how to reference Tolkien does. His Westeros is not Middle Earth. That would have been a mistake even if Martin were not advanced enough in his craft to carve out a world of his own. If you Google Mapped Westeros it wouldn't look like that old Middle Earth map, but if Google zoomed in to particular X Y axis points, they get familiar.

No spoilers, I'll keep it vague: There were moments in the second and third books when I realized a character in Martin's story was basically a 19 year old Aragorn. I liked this character prior to the recognition. After, I loved him. How did I come to think he was young Aragorn, (like River Phoenix playing Indy in the opening scene of "Crusade")? This character's development into a hero takes place at Weathertop and Helm's Deep. Not exactly Weathertop and Helm's Deep --

|

| Helm's Deep even as Aragorn must defend the walls against the Orc Hordes. |

|

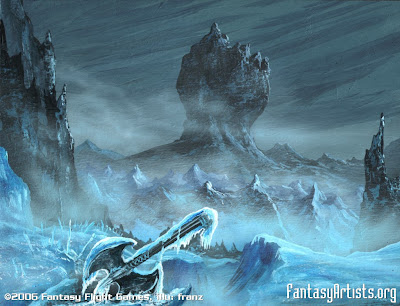

| That's not Weathertop; it's called the Fist of the First Men. An old position of defense for ancient armies. From a GRRM Wiki: The Fist of the First Men is an ancient ringfort built by the First Men in the Dawn Age. There is a ringwall of chest-high grey stone that crowns the top of the steep, stony hill. |

|

| In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, Weathertop (Sindarin Amon Sûl, "Hill of Wind") is of great importance in the history of Middle-earth, as chronicled in The Lord of the Rings, since it was a major fortress of the kingdom of Arthedain, home to one of the seven palantíri, and the site of several battles. The top is still flat and surrounded by a ring of stones. |

|

| The Nazgul as Frodo sees him on Weathertop. |

If a young ranger-type character were slotted to Strider's most iconic moments, than one would/must think that character was an homage to Aragorn. And one would love Martin for it, because unlike twenty thousand bad Tolkien ripoffs, Martin built his 2.0 on the old stones of beloved Middle Earth mise en scène. Throughout A Song of Ice and Fire, Martin has replanted locales from the bible of his genre. Characters are locked in sky cells, not what Saruman called it when he stuck Gandalf on the roof of Orthanc, but, again, you know. In both stories bumbling true-hearted Sams do brave things for their friends, and become unlikely carriers of power.

It's not that Tolkien is Martin's only trick; he is as liberal with his Shakespeare drops and the Prose Edda; he's all but made the perfect mash-up for the 10 year old me. And not just that, but he adds a trick that neither Tolkien nor Norse mythology had any of: GIRLS. Whereas men and their manly places in Ice and Fire are Tolkien, the women of the saga, tiger moms and alpha bitches to make Lady Macbeth and Juliet proud, are straight Shakes.

There is even a lovely old story one character tells another in Ice and Fire of a famous storyteller of the North, who steals a lord's daughter, all of it analogized with winter roses -- by any other name? The storyteller's name is Bill the Bard. Bill the Bard. William the Bard But much of Martin's Shakespearean usage common to many writers -- quite minor things like a character not allied with a lord says to one who is: What fools you kneelers be." A clear rewrite of Puck in Midsummer Night's Dream, "Lord, what fools these mortals be!" -- is just Shake-style leaking in over the years, not by some greater design, as the Tolkien is.

I believe George RR Martin is writing the spiritual sequel to Middle Earth, that he's doing this does not negate all the other reasons Ice and Fire is wonderful, nor all the readers who love this story without having either read Tolkien or care about him; after all, the story is even more densely constructed, with more moving parts and plots, than even Lord of the Rings; there are thousands of pages with no resemblance to Middle Earth. But I think Martin's idea was, from the end of Lord of the Rings, he has pushed the world a thousand years into the future, where Westeros starts out as a very political medieval Europe, with all the corruption, court intrigue, and organized religion as what might have developed in Middle Earth's Fourth Age with magic gone from the world. Martin's Northmen pray to what they call the old gods, faces carved into trees; it isn't a long leap to think perhaps twenty generations back the kin of these Northmen might haps seen armies of real walking tree-men marching over hill and dale. Everything in Westeros is a fine doppelganger to our own world history, with allusions to the War of the Roses, to the Roman Republic; to Macedonian, Celt and Asiatic cultures. But lurking just beneath are the artifacts of a magic world that once was. As Tolkien's saga ends with the dying out of magic in the world, and the onset of modernity; Martin's begins by waking Tolkien's old magic back up, and watching the Age of Men suffer it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment